Thirty years of strobe flash development have ironed out the tendencies to arc-weld switches together or enliven the outer casing, and today there is no shortage of fast recycling, short duration, fully variable flash units with proportional modelling, auto-dumping and everything else you need.

However, the features add to expense. Sometimes what you want is low-cost power - high output without the frills. Here the Prolinca 400 stands almost alone. There's no other 400 Ws unit on the market which has controls limited to on/off, full/half power and slave on/off.

The Prolinca, seen above fitted with standard reflector and honeycomb insert, is British-made as a derivative of Swiss Elinchrom design, and was presumably conceived because an older generation of photographers still expects a standard studio flash to say �400� on the outside and offer 400 joules or Watt seconds from the inside. This is our heritage from the classic Bowens Monolite 400.

The irony is that the Monolite 400 never was 400 Ws and would have serious trouble blowing away the average 1995 160 Ws monobloc, but it could still be controlled right down to quarter power in useful half-stop steps, which made it uniquely desirable during its extended lifetime. In fact, the Mono 400 was so good it outlived its era; its longevity, ready availability and popularity probably delayed the later Bowens flash designs by five years. The standard Prolinca 250 is certainly more powerful than a Mono 400 was even when new; the Prolinca 400 puts out as much light as many older heads which claimed a full kilojoule.

The result is a head which even at half power is virtually unusable in the portrait studio with conventional accessories. Through a 42" shoot-thru nylon brolly, my favorite choice, it yielded an unforgiving f/22.5 or impossible f/32.5 at full wick with standard 160-speed color portrait film. Bounced off the studio ceiling it was perfectly capable of lighting the entire room at f/16.

There are obvious uses for this unit in industrial and commercial work, especially when lighting interiors. My self-set task was to see what we could do with this single head and minimal other equipment to produce a portrait with a five-minute set-up. This is, after all, a head being targeted (in UK advertising, at least) at the portrait and general user.

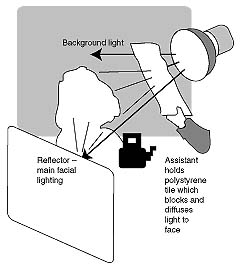

The diagram which follows shows how the lighting was produced. The idea is simple; you

position the flash slightly behind the sitter, and aim it so that it would

normally throw most of its light to one side of the camera. The edge of

the flash is allowed to spill on to the background, where it will tend to

pick up texture or relief; the natural vignetting of the edge of the flash

coverage ensures that the illumination is even.

Half of a large polystyrene ceiling tile is then placed in the centre of the

beam of light, not obstructing the light to the background or the light

coming towards the camera. This puts the sitter's face into shade, with

only minimal light coming through the transulcent tile. A large white

reflector to one side and below the camera collects the remaining

overspilled light and this is bounced back to the sitter's face, providing

the main source of illumination.

One flash head thus provides three lights:

Background light by spill

Side Light through the poly tile

Front Light off the main reflector

The test was made harder by using only minimal space, keeping the sitter close to the Lastolite Monet background, and working with a plain Mamiya 645 and 80mm lens - no filter, no longer lens, no tripod, no vignetting or other attachments.

At half power, the apertures obtained with this single head were around f/8 (bracketed between f/5.6 andf/11) on new Ektacolor Pro Gold 160 film. All exposures were usable and the images had full detail, printing well (by Warrens of Leeds, a major British pro lab).

While the lighting is not perfect and tends to 'butterfly' with too much symmetrical balance, creating too strong a nose and slightly too much contrast in the eyes, it's better than bog-standard 45 degree brolly lighting facially, and far superior on clothes and the background. Only a hair light is missing. The shape and perspective/angle on Debbie's face is not the most flattering, due to the short focal length used very close up, but it does have a bit of directional zip which many straight-on head shots fail to achieve.

Our thanks to Debbie for allowing her picture to be taken in vain for this article. It's a staff policy not to model for our own example shots, but then, if you saw me or Andy you would know why...