In temperatures as high as 120 degrees F and levels of humidity which defy description, I carted the Mamiya kit - camera and four lenses - from Wigan, UK, to Chicago, south to Dallas, south again to San Antonio, and north to Boston, Washington and New York, before crawling back on to a plane home.

Given that the recommended 'storage' conditions for the camera described in the handbook are low humidity and a temperature range from +40 degrees C (105F) to -10C (15F), this was something of a baptism of fire for the instrument. It coped well, the only precaution I took being to ensure that the camera had the opportunity to acclimatise from air conditioned 'normality' to outside temperature before being removed from the bag.

Let me declare myself at the outset - I am a committed Fujica GX680 driver. I love my camera movements, and I have grown too old and lazy to wind film on! However, with the complete Mamiya 7 kit weighing in at little more than half the weight of the GX680 body, magazine and standard 135mm lens - 2.5kg for the complete Mamiya kit, against 4.26kg for the Fujica with standard lens only - my decision to travel light in that heat proved a good one. Everything, including film and a backup Minolta meter - against which to measure the accuracy of the internal metering for the purposes of this test - all fitted into the Rimowa Ultralite bag in which I normally keep my Canon T90 system.

The 7 is the latest in a succession of rangefinder rollfilm cameras introduced by Mamiya over the years. In that respect is has a heritage behind it, and should therefore encapsulate everything the manufacturer has learned from earlier designs. It is a lightweight instrument by 6x7 standards, and comes with a kit of four bayonet mounted lenses - 43mm f4.5, 65mm f4, 80mm f4, and 150mm f4.5 - the least useful, if my practical experiences are anything to go by, being the 80mm.

The 43mm with its rectilinear geometry (above) was one reason for my initial interest, offering a rare and real alternative to the Hasselblad Superwide's 38mm Biogon.

The camera body is in a sort of gun-metal-coloured finish, while the grip and rear door are finished in matt black. Along the edges of the rear door, however, this finish is just paint, unlike the strong plastic protective covering which surrounds the body and the grip. After less than a couple of months of use, this finish is chipping extensively, particularly along the bottom edge of the door.

The 6 x 7 nominal frame size is actually 56mm x 69.5mm, and an optional 35mm panoramic kit is available offering a 24 x 65mm image size, and, of course, the frame counter can cope with either 120, 220, or 35mm film.

With the viewfinder at the extreme left of the camera when viewed from behind, it is most definitely a right-handed right-eyed camera. I am most definitely a left-handed, left-eyed photographer and as such, I found the camera somewhat difficult to get used to. Only with the superb 43mm ultra-wide angle lens - with its own shoe-mounted viewfinder - did I find the camera immediately comfortable to use. Added to that the fact that the 43mm viewfinder has a built-in adjustable optical correction which is not available for the standard viewfinder and the other three lenses (supplementary correction eyepiece lenses are available from +3 to -3 dioptres). It is also the easiest to use for spectacle-wearers like myself.

A shot taken with the 60mm standard wide-angle

With any of the other three lenses, the camera proved much more comfortable for me to use when I was framing vertically, as I could then tuck it in nicely to the left of my nose.

In the hand, the camera is superbly well balanced and, as already mentioned, lightweight. The shoulder strap is attached to two lugs on the viewfinder side of the camera, so it hangs vertically when not in use. This is a well thought out design feature, as it ensures that the excellent well-shaped and firm hand grip on the opposite side of the camera is always free of trailing straps, considerably easing one-handed operation.

The camera body measures in at 159mm across and 112mm high, with a front-to-back body measurement of about 69mm. The design is remarkably uncluttered. The top of the camera has only the hot shoe, shutter speed dial, wind-on lever, frame counter and switch - and they are all tightly grouped on the right side of the top plate. Wind-on is by a single 185 degree stroke. Shutter speeds from 4 seconds to 1/500th are available, together with B, an auto setting (A), and an aperture-lock auto setting (AEL). The latter proved very useful as the metering system, a silicon photo-diode receptor in the viewfinder, seems heavily centre-weighted. Under some conditions it behaves almost like spot-metering, giving some surprising exposures on the first couple of test films when the centre of the subject was unusually bright.

The same half of the baseplate is occupied by the battery compartment - a single 6v 4SR44 battery powers the electronic shutter and meter functions - and by the controls for the ingenious interlinked locks and shutters which facilitate lens-changing. Being in-lens shutters, a protective curtain has to be drawn across the film plane before the lens lock can be released. This is achieved by turning a large key-style ring on the base, and opened again by releasing a sliding lock switch at the foot of the hand grip.

I readily admit to finding this sequence difficult to get into, being such a long-term committed SLR user, although the security it offers is complete. On several occasions I had a momentary confusion as to why the camera would not fire - only to remember eventually that I had not withdrawn the protective blind! OK, while I am admitting things, I ought to come clean and admit � again using my SLR experience as my excuse - to shooting half a roll of film with the lens cap on!

In addition to the hot-shoe, there is a flash socket on the bottom right of the front face, and a conventional cable-release socket at the side of the handgrip beneath the shutter release button. A socket for a mechanical cable release is to be applauded, and my irritation with expensive bespoke electronic cable releases has peppered my test reports over the years. It is both irritating, and against my Scottish principles, to have to buy either an adaptor or a different cable release for each of my cameras.

A minor irritation - a single 1/4" tripod bush is fitted. I usually keep the larger 3/8" screw on my tripod, and would have welcomed the choice, as offered on my Hasselblad and Fujica equipment. You can fit a rather clumsy adaptor on to the baseplate, which although I have not seen it and am therefore into the realms of conjecture, must reduce the rigidity of the tripod-mounted instrument.

The camera is fitted with a fairly sophisticated rangefinder system, using angled cams against the roller wheel, and achieving a greater degree of focusing accuracy than might otherwise be expected with an effective base length of only 34.2mm (60mm base length with a viewfinder magnification factor of 0.57X).

The rangefinder is auto-linked to the 65mm, 80mm and 150mm lenses, with an optical viewfinder for the 43mm. The brightline finder frame is excellent if the camera is presented absolutely square to the eye, but with my left eye requirement already referred to, there were circumstances under which the frame brightness was less than it might have been�and of course the accuracy of framing is also significantly impaired by other than absolutely square-on viewing. The effect of this is slightly reduced by the fact that the viewfinders only show about 85-90 per cent of the actual recorded field of view.

The 150mm lens is an ultra-low dispersion design giving near apochromatic sharpness, but the geometry does not seem to be perfect

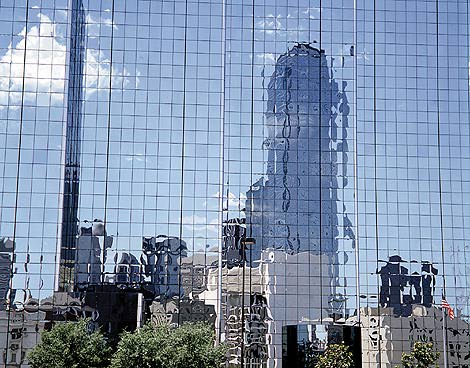

The lenses live up to Mamiya�s claims for them. Optimum rectilinear accuracy is a feature of all focal lengths, thanks to the rangefinder design and the considerable back penetration of the lenses into the camera body. The 43mm in particular allows a spectacularly geometric reading of the sort of architectural subjects which abound in America.

The 43mm allows a big change in composition from a small change in camera viewpoint. This is the largest equestrian sculpture in the world, at Las Colinas in Texas

All the lenses share particularly high contrast, and very low flare. I was also impressed by the ability of the shorter focal lengths especially to operate almost directly into the sun with remarkably low levels of internal reflection - whether or not the lens hoods had been fitted, and I admit to using them rarely.

USS Cassin Young at Charlestown Naval Base, Massachusetts; the 43mm shows no flare despite the into-the-sun angle. The field of view on a 10 x 8" print format is equal to using an 18mm on 35mm

As I hinted earlier, getting to know the metering system is essential, and not always quite as logical as one might have hoped. Especially under low light levels, I found it to prone to underexpose consistently. A series of dusk and night-time shots in downtown Dallas, metered at 2 seconds at f8 actually needed 4 seconds. But at least this seemed consistent and can be compensated for. Compensation of + or - two stops can be set on a scale around the shutter dial.

And my conclusions after this foray into the unknown with the Mamiya 7? It is an easy to handle camera, once the differences from an SLR are taken into account - i.e. once operator error has been factored out of the equation! The optical quality of the lenses is very high, and the sharpness attained could have been enhanced considerably by tripod mounting, but that would rather undermine the whole intention of the camera as a sophisticated instrument for hand-held use.

It was a delight to use, but for me the price is the killer. This is expensive kit by most yardsticks, coming in at �1,233 GB pounds for the body, just under �1,000 for the 80mm lens, and just of �2,110 for the spectacular 43mm. The full kit would set you back a few quid short of �7,000 - and that needs thinking about.