You can currently invest in a Leaf Lumina studio scan-camera for under £3,000 GB pounds; under one year ago we purchased our test sample for a trade price of £4,500 GB when the retail price was over £6,000. The current £2,999 + VAT (European tax at 17.5 per cent) street price includes a 35mm to 6 x 7cm transparency copying unit which was a £1,500 extra a year ago - and which we don't have...

However, we did get a genuine 55mm Micro Nikkor f2.8 lens, as opposed to the Sigma macro being shipped with the Lumina now. The Sigma is more useful as it focuses to 1:1, making 35mm slide scanning practical; the Nikkor is limited to half life size without a tube, and that was not part of the original Lumina package.

A year ago the Lumina could only be purchased in Britain only through Ilford Limited, Scitex Leaf, or one of their specialist dealers. Today it can be found in most mail-order computer catalogues.

The Lumina is probably the best entry opportunity yet for photographers wanting to offer digital photography who have not yet invested in any equipment. In a single unit, it provides all the functions of a desktop print scanner, multiformat transparency scanner and camera scan-back. These three were all separate bits of gear until a couple of years ago, and would have cost you at least £27,000 GB if you wanted to be able to scan prints up to A3, transparencies to 5 x 4, and shoot colour still life.

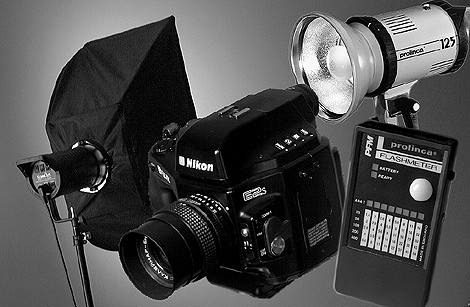

The Lumina needs bright, continuous, daylight balance, IR-free flickerless lighting such as that from the Scandles (left) or Hancocks Softlite (right)

To make the Lumina functional as the heart of a digital studio, you may require some additional lenses, but as it accepts all Nikon manual focus lenses right back to the original F-series finding these is hardly a problem. We bought a 28mm and 135mm Series E secondhand, and a new Russian 100mm f2.8 which proved ideal because of its close 80cm focusing. The overall cost was under £200 for all three.

The Lumina, unlike instant-capture CCD conversions of Nikon camera bodies, gives a full 35mm frame without any constraints on the lens used or working apertures. The scanning sensor is 2,700 pixels wide and only needs a lens with a 50 line pairs per millimetre resolving power; anything higher is wasted. The file size is a maximum of around 25Mb, sufficient for a full A4 page reproduction to catalogue or glossy magazine standard.

Here, the Lumina differs from scanners. A good 35mm to 5 x 4 film scanner at maximum resolution can provide a file anything from 100 to 250Mb in size, allowing A2 sized reproduction. Even a standard sub-£1,000 desktop flatbed scanner can reproduce a 10 x 8 colour print as a 20 x 24" litho poster.

In return, the Lumina has fewer input limitations. With a copy stand and a pair of lights it can photograph a mounted 20 x 16" print, and there is no 'scanner' made - regardless of cost - which can do this. With a flicker-free lightbox the Lumina can copy any size of transparency including large X-rays, and if you can rig up enough lighting power, it is capable of being used to scan through a microscope or macro system. No conventional scanner can reproduce frames of 16mm or 8mm film as well as a Lumina built in to an optical bench.

If you already own a copystand, tripod and some tungsten lighting you can add the Lumina to your studio without much further investment. It requires a Power Mac with a decent amount of memory and something better than a 256-colour display to work efficiently; the approximate street price of such a system with 32Mb RAM and a 15" screen running at 32,000 colours is under £2,000 GB pounds.

In practice, the Broncolor HMI flicker-free lighting first touted as the solution is still the best but very expensive. Special ballasted fluorescent lighting, such as the Scandles head designed by Gary Regester and manufactured in Britain, gives acceptable results without any special infra-red suppressing filters. A more conventionally-shaped soft source, the Softlite from Hancocks, has the same qualities with a substantial heavy-duty construction and bank of bright fluorescent tubes.

Photon Beard (no connection) who manufacture tungsten lights in the useful 250W to 2,000W range report that tests show their redhead and blonde lights to be ideal for use with the £16,000 Dicomed scanning back for 5 x 4 cameras. They are, as a result, selling kits including a couple of 2,000W heads and light control attachments to many buyers of this system.

We have found the 850W redhead lights lacking in power for the Lumina, which is less sensitive than the Dicomed, unless used very close up. This tends to fry the subject. The answer is to use a fair wattage of tungsten, perhaps a couple of 850s and two 2,000s.

A common early error in using the Lumina was to equate banding interference in the shadows with 'under-exposure', as on film or instant CCD cameras. Opening up the lens for extra exposure only makes it worse. Why?

The Lumina has auto-exposure. It can vary the amount of time each pixel in the linear CCD spends gathering light from around 16 milliseconds to over 100ms. If the light-source has any residual flickering at mains frequency, 50MHz to 60MHz or cycles per second, exposure 'times' shorter than 40ms may produce artefacts. Anything shorter than 20ms, one cycle, is guaranteed to give striping or noise even with powerful tungsten lamps where the filament's fluctuation is ironed out by its own capacity to retain heat.

The correct solution to eliminating banding can often be to stop the lens down, forcing the Lumina to make a longer exposure, with each step of the CCD array receiving two or more complete cycles from the light source.

This can result in exposure times far longer than the optimistic three minutes for a full A4 image quoted in advertisements. Five, ten or even fifteen minutes exposure time may be needed, even for smaller file sizes. This is where investment in £2,000-worth of Scandles, Hancocks or similar high-frequency flicker free fluorescent luminaires can pay off.

In our own studio, the Lumina is not a practical device for bulk photography, and this leads to the obvious question - what is?

The cost is over £12,000 so the fact that the only compatible wide-angle zoom is the 20-35mm f2.8D IF AF Nikkor is no barrier. The list of totally compatible lenses is limited; we would advise the Micro-Nikkor 105mm f2.8 and 50mm f1.4D as the best lenses to start with, followed by the 20-35 zoom.

The E2 camera takes what amounts to a full 35mm frame, because of its secondary relay lens system (which is what prevents many common Nikon lens from being used without vignetting or colour artefacts). This also boosts effective filmspeed to a minimum of 800.

The Nikon E2s can work with continuous lighting - the same units as for the Lumina are more than adequate for its high sensitivity - but can also work with flash. In this case, a very small unit such as the 125 joule head shown here is needed

The result is a camera which, used with the right lens, can work right down to the minimum 'controlled aperture' of f38 under normal studio monobloc flash conditions. If you own a portrait lighting flash kit, it will be adequate for small roomsets or still life needing great depth of field with the E2 digital camera.

The motordrive E2s variant will, of couse, provide shutter speeds to stop any action (the filmspeed of the CCD can be boosted to 1600) but the uses of the camera for sports and reporting are not the subject of this feature.

The E2 requires a little more computer hardware; while the Lumina just plugs in to the standard SCSI-2 interface, the Nikon-Fuji uses PCMCIA micro hard disks or memory cards to store its images, and the host computer needs a reader for these. The advantage is that the computer need not be in the studio - the camera has a video-out socket so that you can preview composition on any TV monitor - and a photographer can be working on further catalogue shots while a designer downloads, corrects and crops earlier images. All you need is two PCMCIA memory cards.

This configuration will add £1-2,000 to an existing computer system as the memory cards are far from cheap. Future developments will bring prices down. The advantage of the Nikon-Fuji solution is that the camera can work in any conventional flash studio immediately, is ideal for location shoots and fashion work, and in practice it provides excellent quality as long as the designer doesn't need a double page spread image.

It does not match the Lumina as a means for scanning existing slides and prints, or for ultimate quality full-page repro, and its cost means that without a specific regular contract to handle few people will buy a system. Rental should cost around the same as a Kodak DCS camera - currently £100-150 per day GB.

The Lumina, in contrast, is now affordable as the basis for a toe-in-the-water digital studio.

In the event, a trial Nikon E2 kit was available just in time to use this instead. At standard per shot rates of £35 (standard for big catalogue packshot operations, that is) the E2 could crack 100 white background single column full colour cut-out shots a day - £3,500 of turnover.

Remember, there's no film, no processing, no waiting. Such a shoot would be enough to pay for a camera and computer system and still clear a £10,000 margin. In practice, we agreed a mere fraction of the going rate with our client, as this was an experimental project for all involved. I can, however, reveal that one operator put £1,280-worth of repro work of book covers through a Nikon AX1200 scanner on her first day, work which would once have been scanned at identical cost from 35mm slide copies of the covers - and she had never used the system before in her life.

If you still donÕt think this is ever going to affect the work and businesses of professional photographers, think again, because this is no longer a 'tomorrow' technology - tomorrow arrived the day before yesterday.