Sigma's 1:1 50mm macro AF

Test: David Kilpatrick

Macro lenses are useful alternatives to the 'standard' 50mm in a market

which insists that all photographers want a 28-80mm lens of extremely limited

aperture as their bundled optic. As it is pretty hard to buy an SLR fitted

with a 50mm 2 these days, that very useful and universal lens is often missing

from autofocus kits. Not many new photographers are really aware of just

how much you could do with a 50mm. Most designs worked so well with extension

tubes that fine life-size close ups could be achieved, and when combined

with a decent 2X teleconverter, the 50mm became an ideal 100mm 4 portrait

lens. It had speed for low-light work, a reasonable unaided close focusing

limit, and was often the one lens on which the makers would lavish most

research at lowest cost.

Try to buy yourself a new 50mm 1.4 today, and you're in for a shock. The

price is likely to be as much as your SLR body and probably twice as much

as a midrange zoom. Even a used autofocus 50mm 1.4 for a system like Minolta

or Canon will fetch three figures. Plain, ordinary standard 1.8 lenses have

new price tags approaching £200 if you are foolish enough to order

one separately. Films are much faster than they used to be, grain for grain,

and focusing screens are vastly improved in brightness from the days when

such fast standard lenses were universal. There is a better alternative

p; the 50mm 2.8 macro. With enough speed for low light work, a good

macro lens will perform well at infinity and even better at moderate close-up

distances. The lens itself may be a little heavier and larger than a 50mm

'standard' because of its focusing mount, but it will still compare well

with any zoom.

The Sigma 50mm 2.8 AF macro first came to our attention when Scitex and

Ilford, distributors of the Leaf Lumina scanning camera which we use in

our studio, swapped the 55mm 2.8 Micro Nikkor originally supplied with each

camera for the 50mm AF Sigma. This seems an odd decision p; originally,

the Nikon name was thought essential for the kit to be sold to corporate

buyers, and manual focus was all that was needed. The Micro Nikkor, however,

does not focus right down to life size. Buyers expecting to copy 35mm slides

were surprised to find that the smallest image the Nikkor can fill the frame

with is a 6 x 9cm original. Its 1:2 magnification won't even crop a 6 x

7cm or 6 x 6cm slide to fill the frame.

Enter the Sigma (above left) p; currently selling for little more than

a standard lens, it focuses down to life-size, and uses a radically different

design. The front element is concave and oversized, and the focusing mechanism

extrudes it inside the bayonet mount hood. Unlike the Nikkor (above right)

and my own Minolta AF macro, where the entire deep rim of the lens moves

forward, the Sigma's optics approach the subject unhindered by surrounding

mount. Used on a range of AF and manual SLRs, the Sigma is not fast or particularly

quiet in AF focusing, but in exchange for this degree of resistance you

get a more tactile, substantial manual focus ring and freedom from accidental

MF slippage.

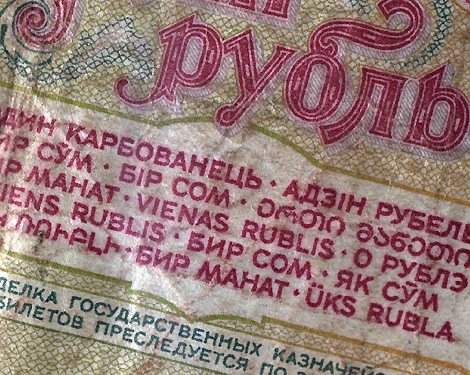

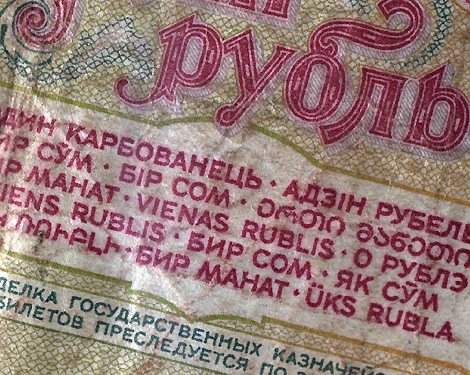

A rouble note - found by Andy in the case of a Kiev camera he bought

in Amsterdam - shot at 1:2 magnification on the Sigma. Yes, we cheated.

It isn't a real photo. It's a Leaf Lumina shot.

The lens is optically first-rate. Concern that a cheaper macro would yield

pincushion distortion disappeared on use. Part of the unusual lens design

appears to be aimed at keeping both a flat field and geometrically accurate

image at all distances. I could not discern any advantage which the Micro

Nikkor might have over the Sigma, other than a slightly brighter contrast

and richer colour rendering.

In terms of finish and control, I found the aperture ring on the Sigma to

be too far from the index dot and not very accurately lined up, so that

I was not sure if I had set half a stop down or was at full aperture. The

Zen matt coated body is not as resistant to wear as Sigma like to believe,

mainly because it and the rubbery bits collect fluff off my old cleaning

cloths used for camera body outsides. It can also collect oily fingerprints,

which wipe cleanly off the enamelled Nikon lens.

If Sigma want to improve this lens, one small thing would make a huge difference

p; extending the close focus to 1.1X life size. Macro lenses are often

used for copy work, and this example is very good for duping 35mm. A true

1:1 is not exactly what's needed, as you normally have to crop a small amount

to cut out mount edges. A 50mm macro with that extra 10% on the close focus

p; surely a small modification p; would be functionally 100% more

useful. The Sigma 50mm AF macro as tested is an entirely new design p;

don't confuse it with earlier models p; and is currently available through

dealers at very keen prices.

Return to Photon May 96 contents