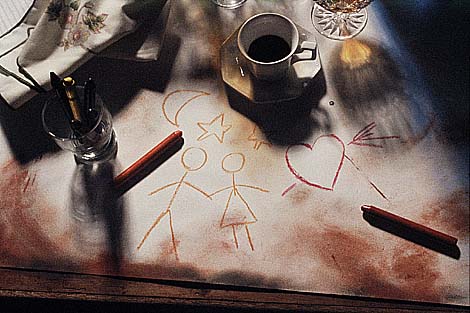

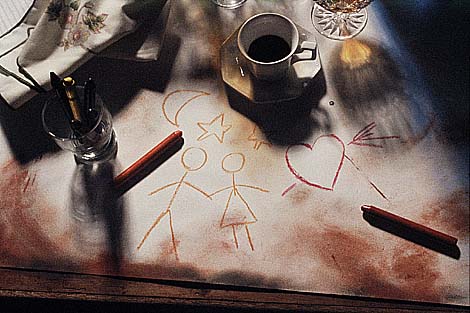

Angus Blackburn was commissioned to produce a 35mm transparency for a hotel restaurant advertisement which was to have strong grain. The budget did not run to artificial grain enhancement, although this can be done using the Add Noise filter for Photoshop, or even better the special noise generation filters in Kai's Power Tools, an add-on package for the same program.

This had to be done conventionally, and as luck would have it, Angus called in for a chat just when we had a fridge full of ultra-fast reversal films nearing their sell-by date. They had already been used, when totally fresh, to test them for lack of grain, purity of color, sharpness and good performance.

Now, slightly older, they were ideal for the reverse test - to find the film which gave the sharpest, biggest grain and moodiest, most distinctive colors. The only 'obselete' film in the batch was Kodak P800/1600, now replaced by Panther P1600X, and the results from this material reflected not only its last-generation status but its length of stay in the freezer.

It cost Angus a fortune in processing because he only got our stock of film on the condition that all five types had to be used and processed at two different pushed speeds.

There were two Scotch Chrome films from the 3M Corporation, the original classic 1000 and the newer push-process P800/3200. Agfa don�t have a 'P' class film, and their 1000RS is better compared to Scotch 1000. Fuji and Kodak only have 'P' films, both actually identical in true speed to the 3M material even though Fuji's is called P1600 and Kodak�s P800/1600. The difference is that Scotch are comfortable with Push 2 and Push 3 E6 processing, for 1600 and 3200 EI, while Fuji and Kodak advise P1 or P2 for 800 or 1600.

For this test, the 1000-speed film were exposed at normal and +1 push, and the 'P' films were all pushed +2 and +3 to 1600 and 3200 speeds. Lighting was by tungsten with correction filters.

The results were interesting, and you can compare the grain in our maximum-size detail enlargements which follow. These were scanned at 5,000 dots per inch on our Leafscan 45 and enlarged to 20X magnification (with very small variations) around 240dpi. We have taken a small section of the images reproduced in the PHOTON printed edition, because these have to be shown at an even higher magnification on the screen; you are viewing the grain here at arounds 65 X magnification, subject to some softening as a result of using JPEG compression.

The comments printed with the scans do not appear in our printed edition (PHOTOpro, shortly to become PHOTON, May 1995) because of limited space. One big advantage of WWW publishing is that we can offer you an expanded version of many features. In the printed edition, the structure of the images is easier to evaluate.

Agfachrome 1000 has never been updated, despite three generations of revised emulsions in the slower 50, 100 and 200 speeds. It has a tight, moderately fine but very crisp grain structure; resolution is not very high.

Agfachrome 1000 pushed by one stop to EI 2000 shows much coarser grain combined with further lowering in sharpness and elimination of fine detail. For a grainy effect, this is not ideal; we were looking for sharp rather than mushy grain.

The classic, original fast slide film after the demise of the now unprocessable GAF 500, 3M's Scotch Chrome 1000 has a dedicated following. Colors were antique, fine detail moderately resolved, and grain the coarsest of any of the unpushed films.

Unlike Agfachrome 1000, pushed Scotch Chrome does not lose the sharpness of its grain. It gets bigger but stays well-defined, and the color does not shift. Contrast is lowered as the shadows acquire a veil of slight fog.

The newer Scotch P800/3200 uses Kodak's E6 'P' process, but be warned - if your lab doesn't have the special times recommended by 3M, which are not the same as Kodak or Fuji, the results will be wrong. The P2 setting at EI 1600 produces very fine, crisp grain with dead neutral color and excellent shadow detail. At a distance, this film looks normal, which is why it's popular with sports and news photographers but not for fashion and portrait work.

Three stops is the limit of the E6 'P' process, and 3M's film is designed to make full use of P3 without any color shift, and with minimal increase in grain size. Though still useful for grain effects at EI 3200, the film remains very normal in appearance, with a slight loss of saturation and shadow detail. 3M P800/3200 is a popular material amongst photographers who use no other 3M products.

Fuji's P-type E6 film is not labelled with alternative speeds, perhaps because the rating of EI 1600 is the optimum. Many users think it is a true 1600 film as a result, unaware that when processed normally it reverts to being a rather soft-contrast EI 400. At 1600, it had grain very similar to Scotch P800/3200, but far superior fine detail resolution and rendering of subtle tones.

At 3200, Fujichrome 1600P changes color, loses most of its subtle qualities, and gets mushy, irregular grain with considerable noise in the shadow zones. The uneven nature of the additional grain makes it unsuitable for quality grain effects, but even at this rating the film performs better, technically, than the one-stop pushed 1000-speed films from Agfa and 3M.

With a warm color rendering and high apparent speed, better reaching EI 1600 than its competitors, Kodak's now superseded E6-P emulsion proved to be marred by an unpleasant speckled grain pattern, which anyone would be forgiven for identifying as an storage fault or bad processing. As all the films were processed professionally by the same lab, the latter seems unlikely. Sharp, but not a very nice film as used. We thought it might be good for grain effects but other failings of an outdated, frozen and then refrigerated stock overcame any possible advantage.

At 3200, the old Kodak film just loses it entirely. Not only is the fog level very high, but the overall color shifts to a violent magenta-plum cast and the grain becomes as uneven as the Fujichrome. The odd speckle effect disappears. Current Panther P1600X material is said to retain normal contrast and detail at 3200, and we will be tested this and the entire Kodak range of current E6 materials (there are five different 100-speed types alone, to cope with various requirements) in a future edition.

The final choice of the photographer was for the fastest Scotch combination - P800/3200 at 3200. The 1000 speed Scotch film had crisper grain, but the colors of the P800/3200 material had extra warmth and there was simply far more shadow and midtone detail. It's interesting that these factors - the quality of the film at this speed - were in the end more important to the feel of the shot than grain alone. The only film to give a poor result was the obsolete Kodak at Push 3 which had high base fog.

When discussing magazines in a small group of European photo mag editors, just after this article appeared in our printed edition, a Dutch colleague asked why we had produced the article at all. He could not understand why any photographer would want to know this, and what the purpose of the test comparison was. To our way of thinking, this kind of evaluation is often beyond the resources of the indidivual photographer seeking a solution to a problem. If a magazine can compare and evaluate products in this way, the reader has a better starting-point for personal experiment. Are we wrong about this?