Cleaning is carried out without chemicals - Jack's tool kit seems to comprise nothing more hi-tech that a variety of paintbrushes, toothbrushes and dentist's tools, with a few soft lead pencils to apply a judicious bit of graphite to cogs and gears.

Cameras are dismantled for cleaning, and carefully rebuilt and tested. Shutters are fired to keep them moving, bellows are opened and closed to avoid them getting too stiff, and where leathercloth coverings need to be reglued, only traditional fish-based glues are used. Everything Jack does is designed to extend the life of the exhibits.

In his white-tiled workshop (above), recently cleaned cameras - visually in a condition which really did deny their age - sat ready to be returned to their displays. White cotton gloves (well, off-white actually) are part of the uniform behind the scenes in a museum dedicated to ensuring that old shutters keep on clicking, and old photographs do not fade away!

Jack's job title is 'Object Cleaner' - no doubt there as to just what he does - and he is just one member of a staff numbering about one hundred people, most of whom are invisible to the three quarters of a million or so who visit the museum each year.

As I walked the public side of the museum, the only staff I saw were three at Reception, one in the IMAX ticket office, several shop and café staff, and a couple of security officers keeping small children out of "The Dead" exhibition - not many more than a dozen in total. All the others work behind the scenes keeping this enormously successful museum up there as perhaps the most visited photography museum in Europe.

The National Museum of Photography, Film and Television is part of the National Museum of Science & Industry - indeed the nucleus of its collection in 1983 came from the Science Museum. Much has changed since then, though, with several million pictures in the collection now.

In addition to the Science Museum collection gathered over nearly a century, the old Daily Herald Photo Library - between two and three million pictures - and several other smaller archives have all been acquired. Here, in row upon row of filing cabinets (above) brought directly from the Herald offices lies the visual history of Britain since 1911. Not just the famous image of Chamberlain holding up the 'piece of paper signed by Herr Hitler' but all the alternative takes of it, are available for serious study. They are also available for commercial use, through the Science & Society Picture Library, part of the commercial arm of the Science Museum in London.

Funding for the NMPFT, like all national museums, is not keeping pace with real costs, and that means that staff have to recognise the pressures that such constraints impose, and look at innovative methods of both acquiring new material and conserving the existing collection. One such innovation is sponsorship, and a fulltime staff member is charged with maximising sponsorship for exhibitions, publications and so on.

Given the huge size of the collection, and the delicacy of some of its contents - the Fox Talbot Collection for a start - considerable costs are involved in storing, cataloguing and conserving it adequately. Joint appointments have been generated with the Metropolitan University of Manchester to bring cataloguers and research assistants in to do vital work on the collections.

Eminent historians, researchers and scientists - names like Larry Schaaf and Mike Ware come high on that list - are involved in important research projects, and have been responsible for major publications on the Talbot material which forms part of the museum’s backbone.

Many new items are offered to the museum each year, from single items to complete collections, from a simple box Brownie to the best of today's contemporary photography. Some of the collections come with their own endowments to ensure their storage, cataloguing, conservation and accessibility. One such is David Hockney's own photography, promised to the museum after his death by the artist himself, together with an endowment to 'manage' it.

In addition, the acquisition of a wide range of items is a regular on-going thing, with curatorial staff constantly keeping an eye on what is being brought to the market. Acquisition is both a passive and an active process - active in the pursuit of specific items to fill gaps in the collection, and passive in the sense of responding to significant images or items of equipment which come up for auction.

The other major committee is the Programme Board, which is charged with overall responsibility for 'public outcomes', and as might be expected, some staff are crucial members of both boards; material generated or commissioned for exhibition might ultimately be acquired for the permanent collection.

Indeed, public outcomes are seen as a very important aspect of the acquisitions policy - letting the public see and enjoy what has been acquired is a central policy of the museum. This has recently evolved into an almost thematic approach to the exhibition policy within the museum. The acquisition of a collection means that cataloguing is essential. If the collection is being thoroughly researched to catalogue it effectively, perhaps an exhibition or a publication might follow.

Typically, this is what is going to happen in 1997 with a major series of events - exhibition, publication and so on - built around the Tony Ray Jones collection acquired by the museum in 1992. Five years from acquisition to exhibition is a relatively short time in museum circles.

1996 will see a major event to celebrate the centenary of the first public cinema performance in Britain, plans for which have been in hand for several years. Indeed, plans are already well in hand to celebrate the centenary of the Box Brownie in the year 2000.

Of course not all the exhibitions the curatorial staff are involved with will take place in Bradford. The museum is a major lender of rare and important equipment and images to countless of other museums. During my visit, the movie camera made by Robert Paul and Bert Acres in 1896 - and which was the actual camera used to film Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee procession in 1897 - was being prepared for loan (above). By the time you read this, it will have arrived at the Museum of London for a major exhibition celebrating the LumiŹres' first public performance of film in Britain in February 1896.

A number of still images spent most of last year at the same Museum, sharing material is a growing area of collaboration amongst museums. Often items requested for loan to another museum involve restoration or stabilisation costs, and increasingly such costs are required to be met by the borrowing venue. Thus the actual loan of items from the permanent collection is seen as a positive force in ensuring its conservation.

The museum is, in some respects, a victim of its own success - a far cry from the press statements by sceptics in the early 80s who could not believe anyone would go to see the Science Museum collection in a disused theatre next to Bradford's ice rink. Every available bit of space in the building is now in use, including a onetime underground car park under the ice rink which became the Kodak Museum a few years ago. Much of the permanent collection can no longer be stored on site, and is warehoused outside Bradford. Additional space is an essential, and plans are afoot for a huge extension, improved storage facilities, additional galleries and much-needed car parking. Much of this hinges on a bid to the Lottery Fund.

What material is actually stored in the Museum Archives itself enjoys state-of-the-art environmental control. In lines of heavy duty storage cabinets, an A-Z of the best of photography's first century and a half is accessible by serious researchers. It was interesting to look at the drawers with red 'disaster' stickers - these are the ones the staff remove first in the case of fire or flood - and see just was priceless material this collection now contains.

A duty curator system ensures that there is always an expert available on the end of the phone to deal with the countless public enquiries received daily. These can range from the most straightforward queries about the age and value of old cameras, to highly specific academic enquiries. As a researcher and photo-historian myself, I am always impressed and appreciative of the willingness of the staff to deal with my varied questions and to offer help. So broad is the collection, and so wide-ranging the staff expertise, almost every project involves them in some way!

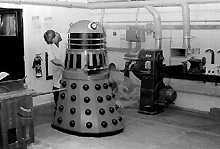

During my visit, Workshop Manager John Wilkinson was proud to show off his Dalek (above) - a new front-of-house fund-raiser. A coin slot in the front of the machine accepts donations, but I was assured the machine took no revenge on visitors who gave too little or nothing at all!

Of course, forPhoton my interest was primarily on the still photography aspect of the museum, but the staff deal just as frequently with enquiries about television and film. The TV galleries especially are extensive and fascinating, and it was interesting to hear that the best way to conserve the old valves and other components of early televisions is often to keep them running constantly. Switch them off and the problems start!

Film is largely handled as a projected medium through the huge IMAX cinema screen, Britain's biggest, and the adjacent Pictureville Cinema. Perhaps when the extensions are built, the evolution of film equipment will get a respectable gallery space.

The Museum also has in inter-active theatre group, and a highly innovative education unit. In addition to offering education visits for schools and colleges, the museum now plays a pivotal role in a number of photograph film and television courses, with curatorial staff adopting the additional role as lecturer from time to time. The commitment to accessibility for all ages and all interests is obvious.

The National Museum of Photography, Film and Television is at 'Pictureville' close to the Jacob's Well roundabout and the Alhambra Theatre, five minutes from Bradford Interchange rail station. Opening times are 10.30 to 6.00 daily except Mondays other than Bank Holidays. Telephone: (+44) 1274 727488.