James Elliott stands alone as a photographer whose vision has not been dimmed by the lure of other arts or the haze of nostalgia (writes editor David Kilpatrick). Most fine-art photographers have bowed to art direction trends, and ape painting styles or movie stills when they're not toning, distressing or non-silver-printing their stuff.

Elliott has remained faithful to camera, lens and film in creating his images, while following a long tradition of photographers in creating physical objects and artworks to include in his images.

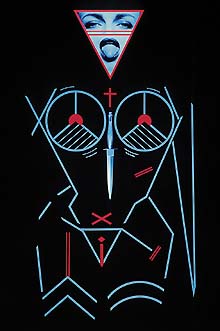

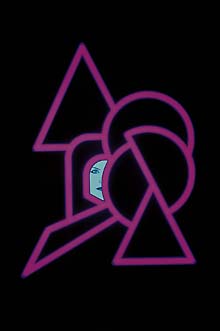

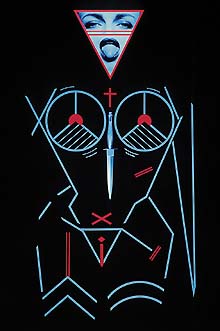

Twenty years ago, James Elliott emerged as the man who devoted months to devising three-dimensional constructions to a flawless standard of finish, then photographing them perfectly on 35mm stock. His early works like Metasphere, 1974+5 could be mistaken for 3D raytraced renderings from a computer - they use the same language of primitives (cones, spheres, cubes, surfaces and perspectives) and have brilliant colours reminiscent of RGB screen images.

In fact, they predate the first raytraced work by a decade. Their antecedents lie in op and pop art and the SFX of films like Barbarella and 2001.

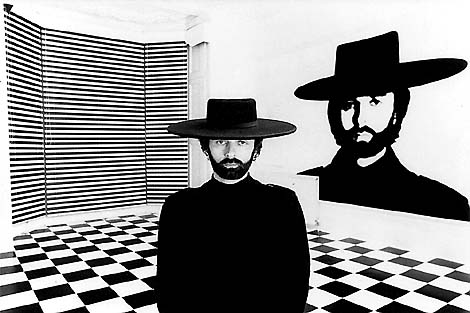

Throughout the 80s and 90s Elliott has remained faithful to his own self-portrait above, as strong an identity as Welles or Hitchcock. He has continued to work incredibly long hours on perfect in-camera exposures in which every grain of film does a precise job. Metasphere took 332 hours to create and the original print sold for $20,000. Superchromatic Spectrosynthesis, 1986, took 400 hours and fetched $19,000. These hand-made silver masked Cibachromes printed by Elliott himself are obsessive in their symmetry, tonality, textures, placement of objects, alignment and all other aspects of control.

Elliott's images encapsulate the culture and technology of the final quarter of this century and collectors pay highly for the work. He believes Metasphere still holds the price record for a direct sale by a living photographer of a single print.

There are some who would say that the effort Elliott puts into the construction and lighting of a shot is destroyed by using anything other than the largest format - say 10 x 8 - and the prints should really be dye-transfers. They're wrong; the future will find precious little true fine art recorded on roll and 35mm formats and printed on contemporary colour materials, and its value will be all the higher because of its scarcity. Elliott worked briefly with 5 x 4, didn't enjoy it; when film quality made a quantum leap in the early 1980s he found his 35mm and Bronica 6 x 4.5cm originals more than adequate.

Elliott is sometimes dismissed as a serious photographer by the advertising fraternity; he hasn't produced Polaroid emulsion-transfer prints or stuff where rebates and clip marks get printed for effect. He has never joined the consensus that the only way to light everything is with splashes of tungsten light across textured surfaces mainly lit by diffused flash.

What he actually produces is lit with such simplicity that the viewer is not conscious of lighting. The result emphasises colour, form and composition.

Recently, he's pursued a politically incorrect line in video production and publicity stunts, launching his last London exhibition with appearances by Hollywood starlets even Howard Hughes couldn't have engineered a solution for. This is phase of his work you may see covered in Penthouse but not here.

James Elliott started taking photographs seriously 'around 1967 or 1968', growing up in the relative isolation of a Devon, UK, village. He never attended college, and never worked as an assistant. By 1975 he was well-known for his surreal montages and meticulous constructions - several years before set-building, spurred on by Benson and Hedges and others, became a standard part of photographic practice. His breakthrough sale of Metasphere in 1974 as a fine art print was a result of his own judgment that this market would one day be an important one for photographers. Many people were sceptical about the hype necessary to make an impression in art circles. Moreover, magazine editors around the end of the 1970s didn't like the art world taking over from the press as patrons of photography.

Despite the risk of being an 'outsider' Elliott never once deviated from his path as a creator of images for sale as art originals. In retrospect, James Elliott successfully forsaw the future of photo-art sales in London, New York and Paris. Yet, with a few exceptions like William Eggleston and Martin Parr, most other living photographers only sell prints when their stuff is in period style or mucked around to avoid resembling a camera image. Unashamedly photographic work is rarely bought.

So, I have to take my hat off to a man who's never once changed his. Elliott has created and sold pure photography as fine art for twenty years, and very few of his contemporaries can match that.